🦃 Enjoy Thanksgiving & BFCM with FREE SHIPPING!

Silicone Flower Pulling Toy

My First Feeding Set (Farm)

My First Feeding Set (Farm)

View all products

Babies Love Our Products

My First Blocks Mini

$29.99

Unit price / per

My First Blocks Mini

$29.99

Unit price / per

My First Blocks Mini

$29.99

Unit price / per

My First Blocks Mini

$29.99

Unit price / per

My First Blocks Mini

$29.99

Unit price / per

My First Feeding Set (Farm)

My First Feeding Set (Farm)

My First Feeding Set (Farm)

My First Feeding Set (Farm)

My First Feeding Set (Farm)

Drop & Roll Tower

$29.79

Unit price / per

Drop & Roll Tower

$29.79

Unit price / per

Drop & Roll Tower

$29.79

Unit price / per

Drop & Roll Tower

$29.79

Unit price / per

Drop & Roll Tower

$29.79

Unit price / per

My First Blocks

$39.80

Unit price / per

My First Blocks

$39.80

Unit price / per

My First Blocks

$39.80

Unit price / per

My First Blocks

$39.80

Unit price / per

My First Blocks

$39.80

Unit price / per

My First Feeding Set (Safari)

My First Feeding Set (Safari)

My First Feeding Set (Safari)

My First Feeding Set (Safari)

My First Feeding Set (Safari)

My First Tea Set

$25.00

Unit price / per

My First Tea Set

$25.00

Unit price / per

My First Tea Set

$25.00

Unit price / per

My First Tea Set

$25.00

Unit price / per

My First Tea Set

$25.00

Unit price / per

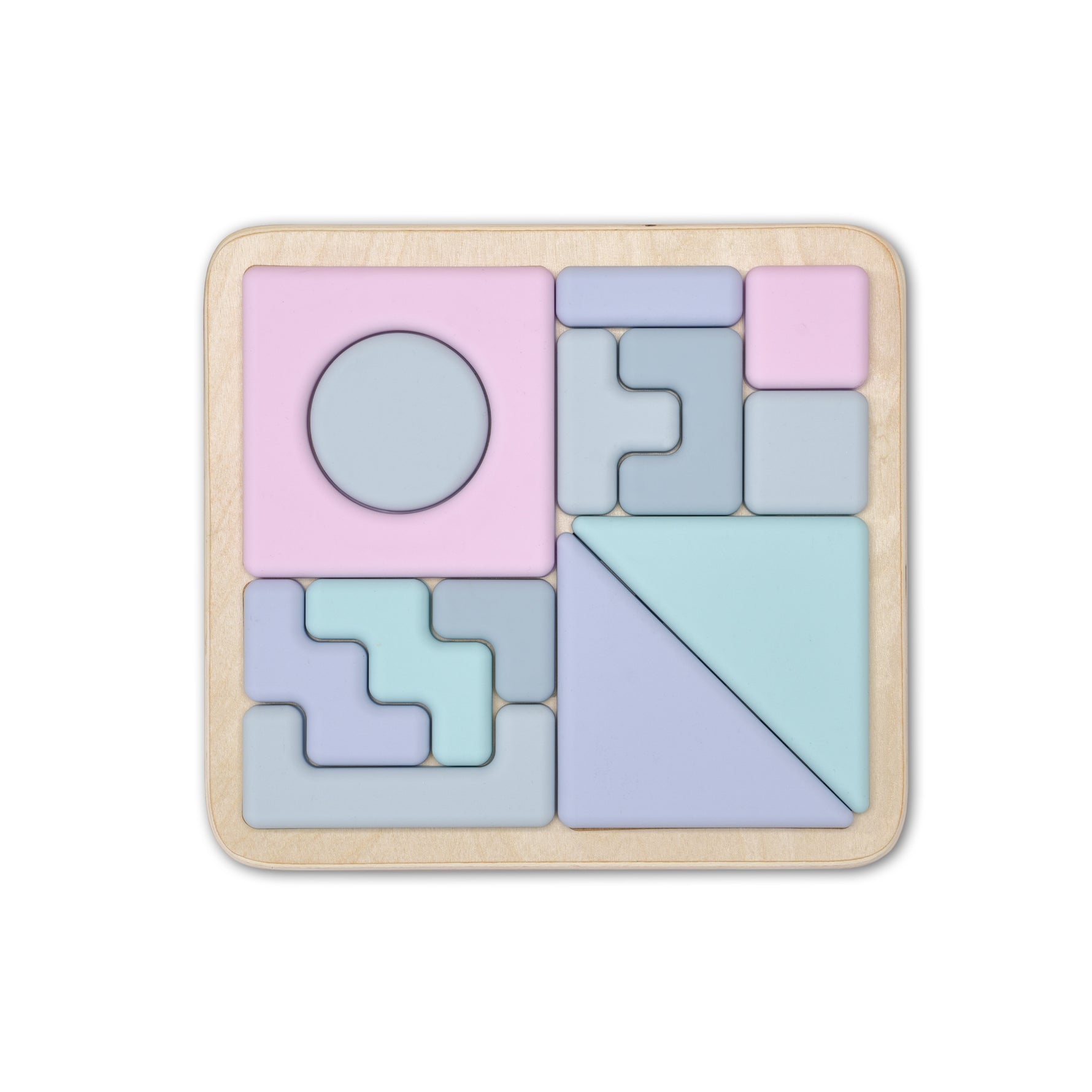

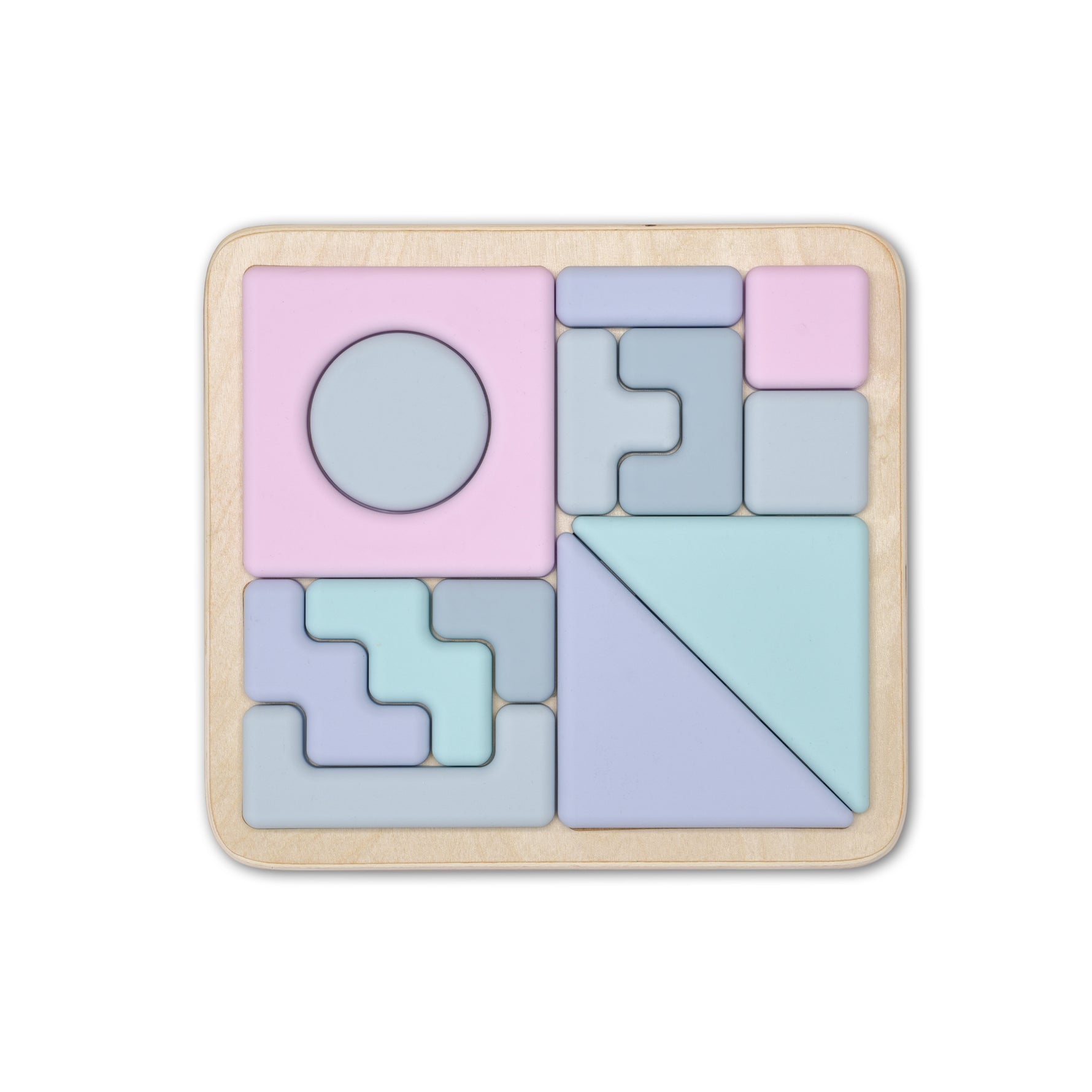

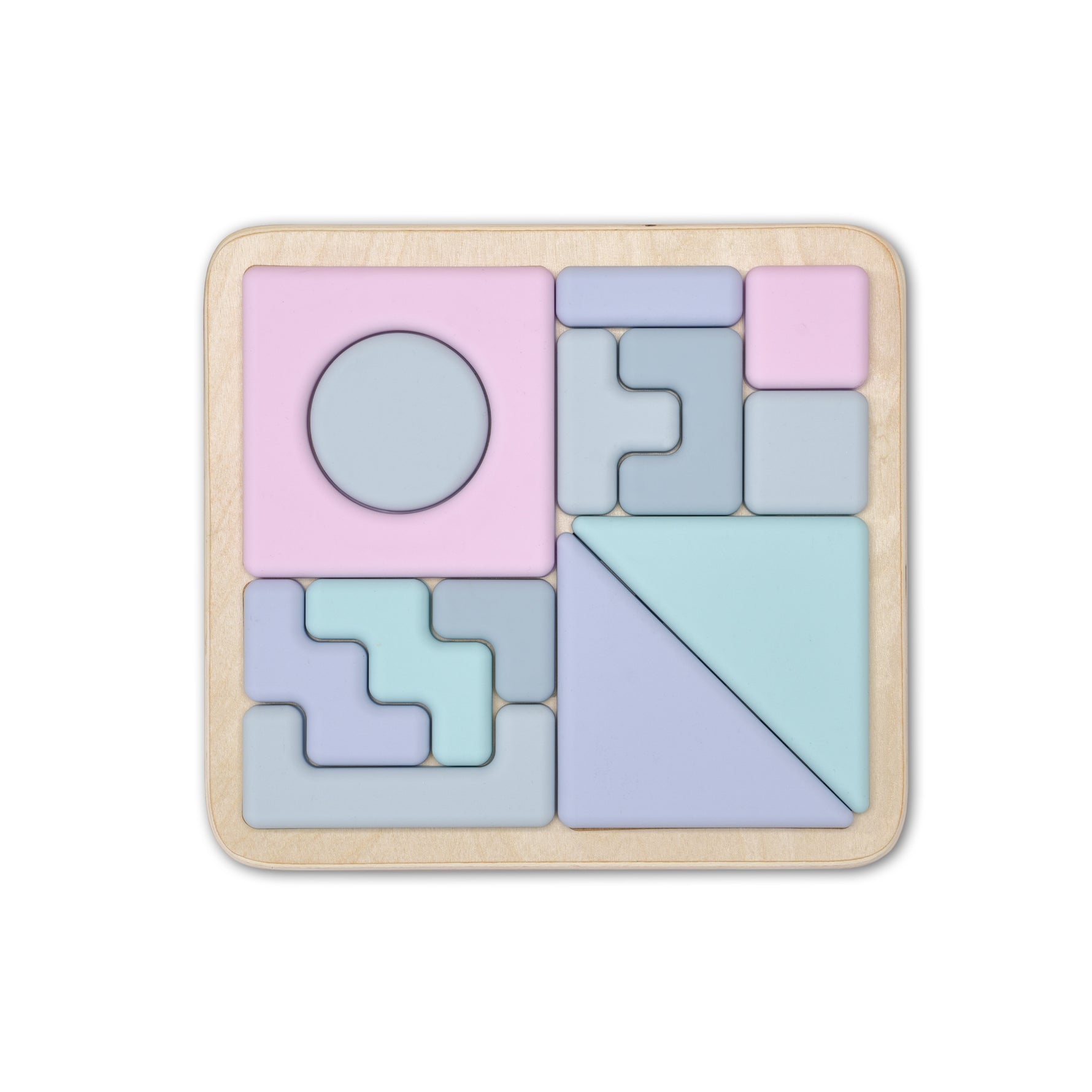

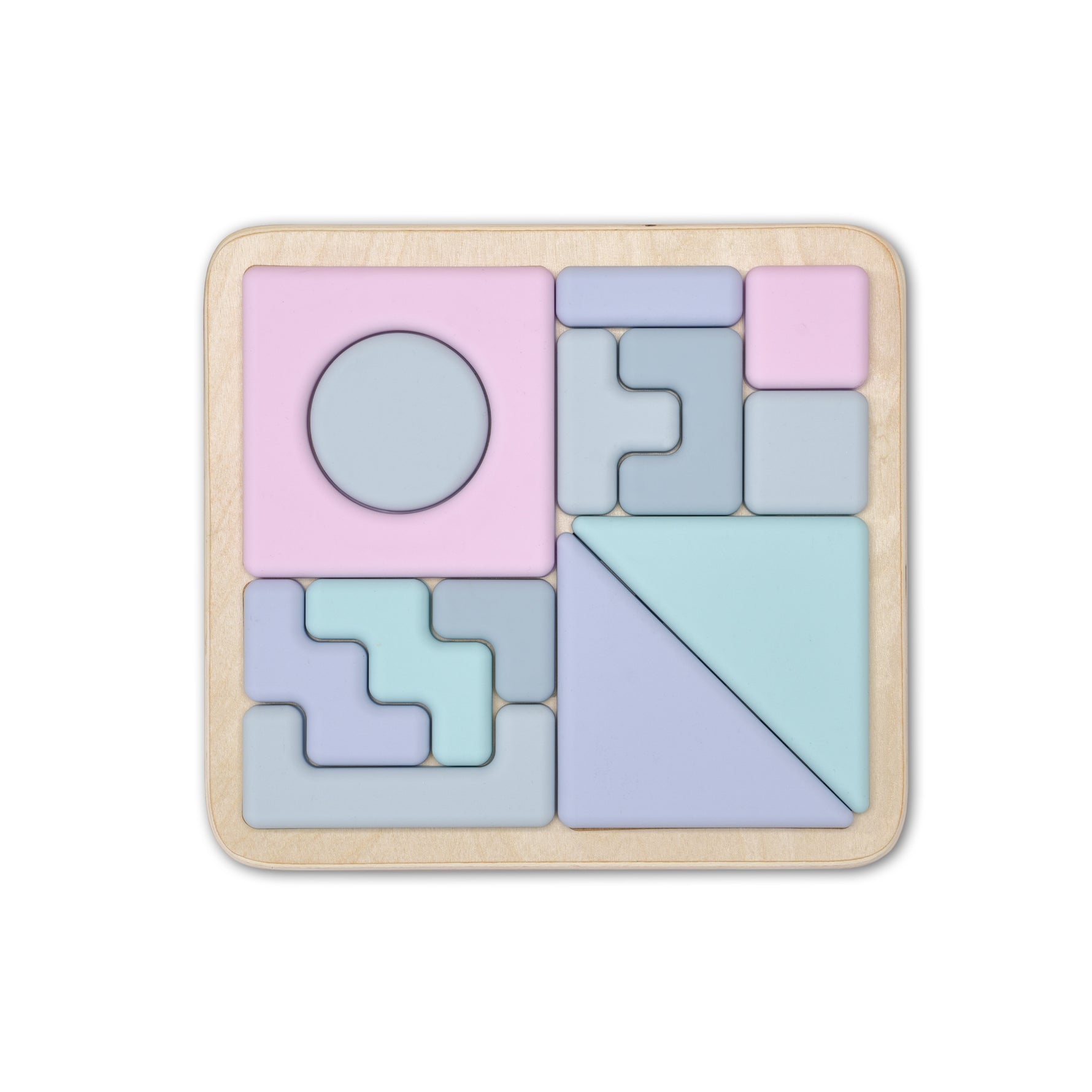

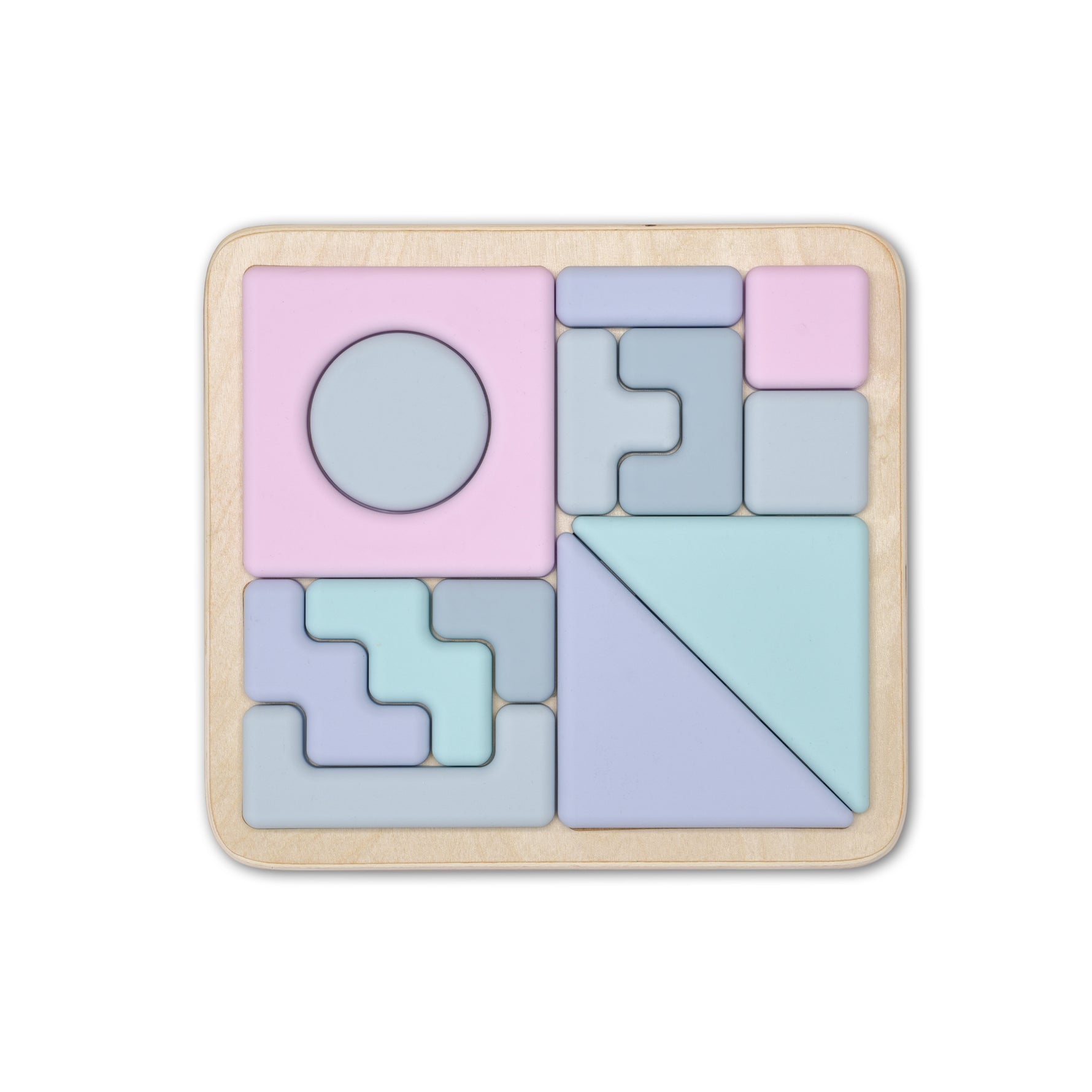

Smart Fit Puzzle

$19.99

Unit price / per

Smart Fit Puzzle

$19.99

Unit price / per

Smart Fit Puzzle

$19.99

Unit price / per

Smart Fit Puzzle

$19.99

Unit price / per

Smart Fit Puzzle

$19.99

Unit price / per

Silicone Suction Spinners - 3 Pack

$13.43

Unit price / per

Silicone Suction Spinners - 3 Pack

$13.43

Unit price / per

Silicone Suction Spinners - 3 Pack

$13.43

Unit price / per

Silicone Suction Spinners - 3 Pack

$13.43

Unit price / per

Silicone Suction Spinners - 3 Pack

$13.43

Unit price / per

My First Feeding Set (Forest Friends)

My First Feeding Set (Forest Friends)

My First Feeding Set (Forest Friends)

My First Feeding Set (Forest Friends)

My First Feeding Set (Forest Friends)

Stacking Teething Rings

$15.99

Unit price / per

Stacking Teething Rings

$15.99

Unit price / per

Stacking Teething Rings

$15.99

Unit price / per

Stacking Teething Rings

$15.99

Unit price / per

Stacking Teething Rings

$15.99

Unit price / per

Tummy Time Mirror

Tummy Time Mirror

Tummy Time Mirror

Tummy Time Mirror

Tummy Time Mirror

Silicone Baby Bib - 2 Pack

$12.99

Unit price / perSilicone Baby Bib - 2 Pack

$12.99

Unit price / perSilicone Baby Bib - 2 Pack

$12.99

Unit price / perSilicone Baby Bib - 2 Pack

$12.99

Unit price / perSilicone Baby Bib - 2 Pack

$12.99

Unit price / per

Fit & Learn Geo Puzzle

$14.99

Unit price / per

Fit & Learn Geo Puzzle

$14.99

Unit price / per

Fit & Learn Geo Puzzle

$14.99

Unit price / per

Fit & Learn Geo Puzzle

$14.99

Unit price / per

Fit & Learn Geo Puzzle

$14.99

Unit price / per

Silicone Bear Divider Plates

$12.99

Unit price / per

Silicone Bear Divider Plates

$12.99

Unit price / per

Silicone Bear Divider Plates

$12.99

Unit price / per

Silicone Bear Divider Plates

$12.99

Unit price / per

Silicone Bear Divider Plates

$12.99

Unit price / per

Smoothie Cup

$14.99

Unit price / per

Smoothie Cup

$14.99

Unit price / per

Smoothie Cup

$14.99

Unit price / per

Smoothie Cup

$14.99

Unit price / per

Smoothie Cup

$14.99

Unit price / per

Free Shipping

Because Every Parent Deserves Easy

Easy Returns

30-Day Money Back Guarantee

Baby Safe

No Harmful Chemicals

Thoughtful Design

Pure Care for Tiny Cubs

Blog posts

How to Clean & Care for Silicone Baby Products During Holiday Travel

Best Wooden Blocks for Babies 6+ Months: A Complete Guide for Parents

Tips for Establishing a Sleep Routine

Help & Support

© 2025,

Baby Bertie.